Book Review: Twilight Warriors by James Kitfield

Twilight Warriors focuses on the cadre of leaders who came of age during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and forged what the author describes as a new “American Way of War.” Kitfield, a senior fellow at the Center for the Study of the Presidency and Congress and a recognized authority on the US national security apparatus (Prodigal Soldiers, 1997, War and Destiny, 2005) presents a well-researched argument based on interviews and personal experience overseas, asserting that over the course ten years of war the US national security apparatus has developed a new and devastatingly effective approach to war. This new approach is based on techniques “find, fix, finish, exploit, and analyze” pioneered by Generals Stanley McCrystal and Mike Flynn in Iraq. Twilight Warriors describes the professional development and interaction of these and other innovators as they succeed and eventually occupy some of the highest positions in the national security structure. A new cooperative inter-agency culture is also a hallmark of the tactics employed not only in Afghanistan and Iraq, but globally as the center-piece of an extremely effective US counter-terrorism strategy. Kitfield’s work is insightful, informative and timely. He includes in his analysis the rise of ISIS in Syria and Iraq, the immigration issues in Europe, and the recent Paris and Brussels terrorist attacks. This new analysis of US counter-terrorism strategy is required reading for anyone with a personal or professional interest in the subject.

Twilight Warriors focuses on the cadre of leaders who came of age during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and forged what the author describes as a new “American Way of War.” Kitfield, a senior fellow at the Center for the Study of the Presidency and Congress and a recognized authority on the US national security apparatus (Prodigal Soldiers, 1997, War and Destiny, 2005) presents a well-researched argument based on interviews and personal experience overseas, asserting that over the course ten years of war the US national security apparatus has developed a new and devastatingly effective approach to war. This new approach is based on techniques “find, fix, finish, exploit, and analyze” pioneered by Generals Stanley McCrystal and Mike Flynn in Iraq. Twilight Warriors describes the professional development and interaction of these and other innovators as they succeed and eventually occupy some of the highest positions in the national security structure. A new cooperative inter-agency culture is also a hallmark of the tactics employed not only in Afghanistan and Iraq, but globally as the center-piece of an extremely effective US counter-terrorism strategy. Kitfield’s work is insightful, informative and timely. He includes in his analysis the rise of ISIS in Syria and Iraq, the immigration issues in Europe, and the recent Paris and Brussels terrorist attacks. This new analysis of US counter-terrorism strategy is required reading for anyone with a personal or professional interest in the subject.

H305: Ends Ways and Means in Vietnam

Through the Tet offensive in 1968, some have argued that the United States did not have a firm strategy in Vietnam. For a strategy to be coherent it must logically connect ends, ways, and means. If you assume that the U.S. end was a stable South Vietnamese government, and that the U.S. had the means to achieve that end, how do you evaluate the ways the U.S. pursued the strategy? Some things to think about: What were the U.S. ways? Were they logically connected to the end? What was missing from the U.S. strategy?

Through the Tet offensive in 1968, some have argued that the United States did not have a firm strategy in Vietnam. For a strategy to be coherent it must logically connect ends, ways, and means. If you assume that the U.S. end was a stable South Vietnamese government, and that the U.S. had the means to achieve that end, how do you evaluate the ways the U.S. pursued the strategy? Some things to think about: What were the U.S. ways? Were they logically connected to the end? What was missing from the U.S. strategy?

H302: Its the Economy Stupid… Comrade!

Maoist revolutionalry war theory puts the priority of effort on the political line of operations. Our experience with our own domestic politics indicates that the key to successful politics is the economy. Therefore… maybe:

Maoist revolutionalry war theory puts the priority of effort on the political line of operations. Our experience with our own domestic politics indicates that the key to successful politics is the economy. Therefore… maybe:

COIN = Politics

Politics = Economy

.’. COIN = Economy

Consider this: Do populations whose economic aspirations are being met ever revolt?

H302 Revolutionary War and the US Military in the 21st C

There are a wide variety of insurgent groups who have operated against U.S. forces in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2003. Very few, if any, have followed a Maoist strategy. Some analysists believe that this fact proves that Mao’s Revolutionary War theory is not relevant to the type of adversaries faced by the U.S. in the GWOT. Are these analysists correct?

There are a wide variety of insurgent groups who have operated against U.S. forces in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2003. Very few, if any, have followed a Maoist strategy. Some analysists believe that this fact proves that Mao’s Revolutionary War theory is not relevant to the type of adversaries faced by the U.S. in the GWOT. Are these analysists correct?

As the US military moves forward many believe that the age of Revolutionary war is past, and even if its not, it does not represent an strategic threat to US national interests. Therefore, the US military should leave revolutionary war to special operations forces, and the bulk of the US military resources, to include doctrine, training and organization, should be focused on opposing conventional and nuclear threats from China, Russia and North Korea.

How important to future war is revolutionary war, and to what degree should the US military establishment prepare itself to fight revolutionary war?

Afghanistan…Vietnam??

Afghanistan is dramatically different than Iraq. A quick look at geography, history, and demographics, not to mention the nature of the adversary and the geopolitical setting all describe a completely different operating environment. Also, with the change of political parties in the U.S. and with the U.S. facing significant economic challenges, the domestic U.S. scene is completely different. Some analysts believe that these circumstances make Afghanistan a more significant challenge than Iraq ever was. Commentators Ralph Peters and French MacLean have described their views on the strategic situation. Is Afghanistan more like Vietnam than Iraq? What are the parallels of Afghanistan to Vietnam? Is Afghanistan doomed to end the same way Vietnam did, or are the situations different enough, and the US capabilities and strategies different enough, for Afghanistan to survive as a nation state unlike South Vietnam?

Afghanistan is dramatically different than Iraq. A quick look at geography, history, and demographics, not to mention the nature of the adversary and the geopolitical setting all describe a completely different operating environment. Also, with the change of political parties in the U.S. and with the U.S. facing significant economic challenges, the domestic U.S. scene is completely different. Some analysts believe that these circumstances make Afghanistan a more significant challenge than Iraq ever was. Commentators Ralph Peters and French MacLean have described their views on the strategic situation. Is Afghanistan more like Vietnam than Iraq? What are the parallels of Afghanistan to Vietnam? Is Afghanistan doomed to end the same way Vietnam did, or are the situations different enough, and the US capabilities and strategies different enough, for Afghanistan to survive as a nation state unlike South Vietnam?

Ends, Ways, and Means in Vietnam

Through the Tet offensive in 1968, some have argued that the United States did not have a firm strategy in Vietnam. For a strategy to be coherent it must logically connect ends, ways, and means. If you assume that the U.S. end was a stable South Vietnamese government, and that the U.S. had the means to achieve that end, how do you evaluate the ways the U.S. pursued the strategy? Some things to think about: What were the U.S. ways? Were they logically connected to the end? What was missing from the U.S. strategy?

Through the Tet offensive in 1968, some have argued that the United States did not have a firm strategy in Vietnam. For a strategy to be coherent it must logically connect ends, ways, and means. If you assume that the U.S. end was a stable South Vietnamese government, and that the U.S. had the means to achieve that end, how do you evaluate the ways the U.S. pursued the strategy? Some things to think about: What were the U.S. ways? Were they logically connected to the end? What was missing from the U.S. strategy?

Economic Warfare: The American Way of War

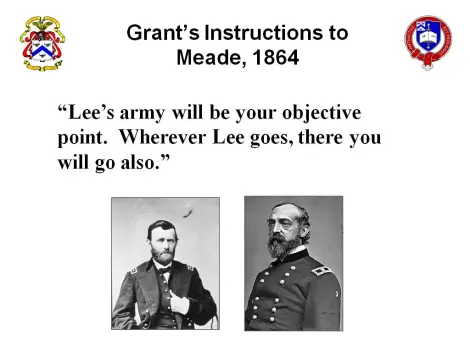

The American Civil War vividly demonstrated how the products of the industrial revolution, the rifled musket, steam powered trains and ships, the telegraph, banking, and mass production manufacturing techniques changed tactical and operational warfare. Less noticable was the way in which the economic base of a country became an important aspect of its war making capability. Limited economic base meant limited war making capability while a large robust economic base meant a large war making capability. General Grant consiously developed his attritition strategy followed in the last eighteen months of the war based on his understanding of the economic advantages of the Union. Simply put, the Union could sustain losses of manpower and material and the South could not. Thus, tactical and operational victory, though desired, was not necessary to winning the war. Continuous fighting was necessary to make this happen –not continuous tactical victory. Thus Grant’s guidance to his subordinate :

Though focused tactically on battle, the purpose of battle was not to achieve tactical victory, but rather to deplete Southern resources, regardless of tactical victory. Thus, there was no direct link between military tactical victory and strategic victory. Military operations were necessary to enable the leveraging of the Union’s economic advantage, but the economic advantage was what was decisive not the supporting military campaign.

Grant focused on destroying the Southern Army, and then Southern governance. Nothing done in the Civil War or after addressed the third aspect of Clausewitz’s trinity –the passion of the people. Some argue that this was the reason for the failure of Reconstruction and domination of former Confederates of the South after the war.

Historian Russel Weigley sees the Civil War as a template for an “American Way of War:” “The Civil War tended to fix the American image of war from the 1860s into America’s rise to world power at the turn of the century, and it also suggested that the complete overthrow of the enemy, the destruction of his military power, is the object of war.”

Does Weigley’s template for the American Way of War still apply today? Are we pursuing a Grant model strategy in Afghanistan focused on insurgents and insurgent leadership, and ignoring the “passion” that supports the insurgency?

How does a strategy address the “passion” aspect of war? Is it part of the military strategy or should it be part of the national strategy? Who in government is the lead for attacking the enemy’s passion?

Afghanistan…Vietnam??

Afghanistan is dramatically different than Iraq. A quick look at geography, history, and demographics, not to mention the nature of the adversary and the geopolitical setting all describe a completely different operating environment. Also, with the change of political parties in the U.S. and with the U.S. facing significant economic challenges, the domestic U.S. scene is completely different. Some analysts believe that these circumstances make Afghanistan a more significant challenge than Iraq ever was. Commentators Ralph Peters and French MacLean have described their views on the strategic situation. Is Afghanistan more like Vietnam than Iraq? What are the parallels of Afghanistan to Vietnam? Is Afghanistan doomed to end the same way Vietnam did, or are the situations different enough, and the US capabilities and strategies different enough, for Afghanistan to survive as a nation state unlike South Vietnam?

Afghanistan is dramatically different than Iraq. A quick look at geography, history, and demographics, not to mention the nature of the adversary and the geopolitical setting all describe a completely different operating environment. Also, with the change of political parties in the U.S. and with the U.S. facing significant economic challenges, the domestic U.S. scene is completely different. Some analysts believe that these circumstances make Afghanistan a more significant challenge than Iraq ever was. Commentators Ralph Peters and French MacLean have described their views on the strategic situation. Is Afghanistan more like Vietnam than Iraq? What are the parallels of Afghanistan to Vietnam? Is Afghanistan doomed to end the same way Vietnam did, or are the situations different enough, and the US capabilities and strategies different enough, for Afghanistan to survive as a nation state unlike South Vietnam?

Economic Warfare: The American Way of War

The American Civil War vividly demonstrated how the products of the industrial revolution, the rifled musket, steam powered trains and ships, the telegraph, banking, and mass production manufacturing techniques changed tactical and operational warfare. Less noticable was the way in which the economic base of a country became an important aspect of its war making capability. Limited economic base meant limited war making capability while a large robust economic base meant a large war making capability. General Grant consiously developed his attritition strategy followed in the last eighteen months of the war based on his understanding of the economic advantages of the Union. Simply put, the Union could sustain losses of manpower and material and the South could not. Thus, tactical and operational victory, though desired, was not necessary to winning the war. Continuous fighting was necessary to make this happen –not continuous tactical victory. Thus Grant’s guidance to his subordinate :

Though focused tactically on battle, the purpose of battle was not to achieve tactical victory, but rather to deplete Southern resources, regardless of tactical victory. Thus, there was no direct link between military tactical victory and strategic victory. Military operations were necessary to enable the leveraging of the Union’s economic advantage, but the economic advantage was what was decisive not the supporting military campaign.

Grant focused on destroying the Southern Army, and then Southern governance. Nothing done in the Civil War or after addressed the third aspect of Clausewitz’s trinity –the passion of the people. Some argue that this was the reason for the failure of Reconstruction and domination of former Confederates of the South after the war.

Historian Russel Weigley sees the Civil War as a template for an “American Way of War:” “The Civil War tended to fix the American image of war from the 1860s into America’s rise to world power at the turn of the century, and it also suggested that the complete overthrow of the enemy, the destruction of his military power, is the object of war.”

Does Weigley’s template for the American Way of War still apply today? Are we pursuing a Grant model strategy in Afghanistan focused on insurgents and insurgent leadership, and ignoring the “passion” that supports the insurgency?

How does a strategy address the “passion” aspect of war? Is it part of the military strategy or should it be part of the national strategy? Who in government is the lead for attacking the enemy’s passion?

Ends, Ways, and Means in Vietnam

Through the Tet offensive in 1968, some have argued that the United States did not have a firm strategy in Vietnam. For a strategy to be coherent it must logically connect ends, ways, and means. If you assume that the U.S. end was a stable South Vietnamese government, and that the U.S. had the means to achieve that end, how do you evaluate the ways the U.S. pursued the strategy? Some things to think about: What were the U.S. ways? Were they logically connected to the end? What was missing from the U.S. strategy?

Through the Tet offensive in 1968, some have argued that the United States did not have a firm strategy in Vietnam. For a strategy to be coherent it must logically connect ends, ways, and means. If you assume that the U.S. end was a stable South Vietnamese government, and that the U.S. had the means to achieve that end, how do you evaluate the ways the U.S. pursued the strategy? Some things to think about: What were the U.S. ways? Were they logically connected to the end? What was missing from the U.S. strategy?

-

Archives

- November 2018 (1)

- October 2018 (5)

- September 2018 (4)

- August 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (3)

- January 2018 (6)

- November 2017 (2)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (5)

- August 2017 (2)

- March 2017 (6)

- January 2017 (6)

-

Categories

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS